Whitman, Melville, and Civil War Poetry

High School / History / Civil War

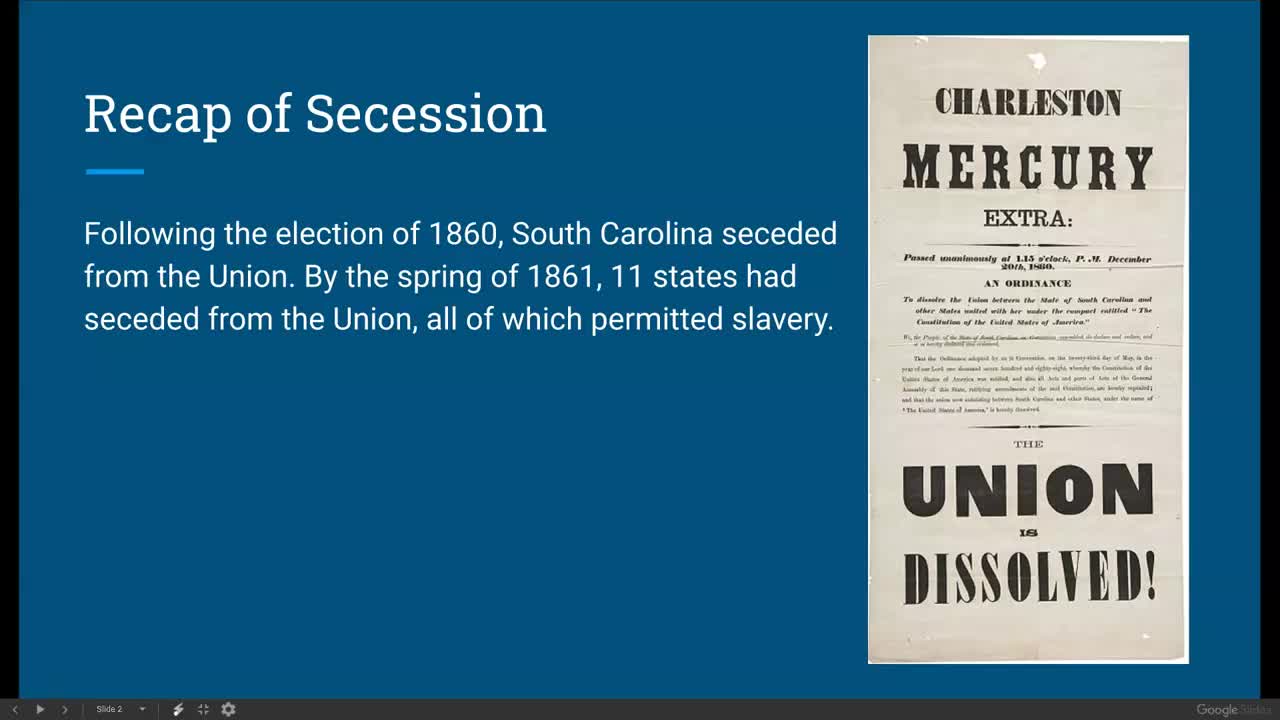

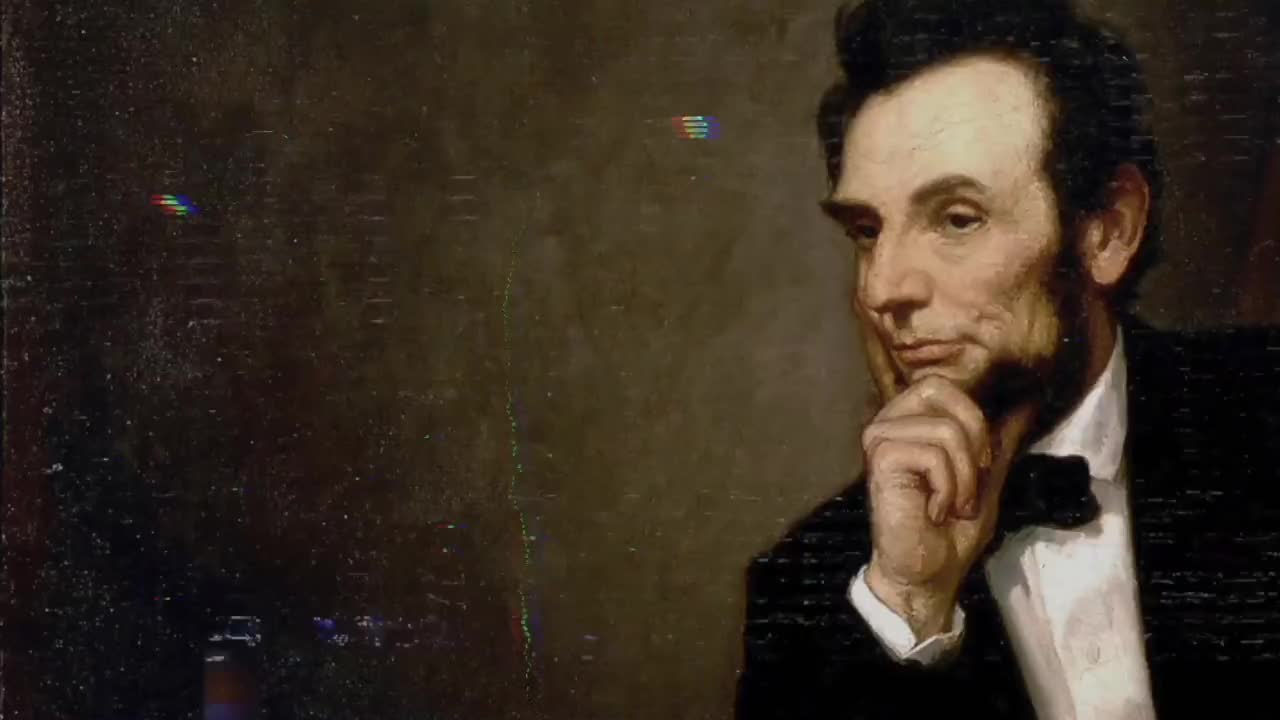

Okay. So today I'm going to be talking about and let me go ahead and share this screen. The poetry of the Civil War and specifically Walt Whitman and Herman Melville and their Civil War poetry. And there's a couple of reasons that I thought this would be a good topic to discuss. So first of all, today is Juneteenth. So it marks the liberation of the final slave colony in Galveston, Texas, in the 1865. And also, there's this question that I thought we could consider throughout the course of this presentation, which is how does one step out of an event to memorialize it and how can we eulogize the present in a sense? So that living through a present in which we sense that things will never be the same as not the same as understanding the changes that will be brought. So we can see in this poetry, the poets themselves trying to come to terms not only with the war and what the war means, but also how the war is being a watershed moment is going to affect art. And so that the art of poetry is attempting to engage with the meaning of the war, but then recognizing as well that the war is going to affect the way in which poetry is written. Okay, so a few things to put Civil War in historical context. So initially, most believe the war would end quickly and with a few casualties. So there's a phrase now this was mostly true in the south because they thought the northerners to be very weak and without a great cause to fight for. And so there was a phrase that was said by a lot of other politicians, quote I will drink every drop of blood spilled in this war, basically saying that they believe that none would be spilled. And it was uttered by so many politicians that it's now possible to trace the quote back to its originator. Of course, it's not true at all. By the end of the war, 750,000 were dead and possibly as high as 850,000 deaths. To put that number in perspective, one fourth of soldiers who fought in the war died. So a full quarter of all sorts of soldiers who fought in the war died. It ended up being about 2.5% of the entire American population at the time. So if the war were to occur today, the number of deaths would be upwards of 6.5 million. More Americans died in the Civil War than all other wars combined. So it's 7 times as many Americans die as I had in World War I, three times as many as died in Vietnam and 30 times as many died in the Revolutionary War. And then one thing to bear in mind which will come up a little bit later with one of the poems is two thirds of all deaths in the Civil War were not on the battlefield, in fact, that they were from disease. So germ theory and antisepsis was not yet developed. Who fought in the war and where do they fight? It was mostly boys, mostly young boys who fought in the war. A lot of college aged boys who would abandon the schoolroom or if they worked on their parents farm, the plow and they saw it as a kind of great adventure. By entering into a war, there was a belief that young men could participate in the modern equivalent of the epics that they had read in school. And then where was the world fight? It was fought over land that was mostly unoccupied. And many of these men had never left their hometown. So there were really seeing uncharted territory and had never themselves traveled before. And then significantly as well. It was the first photographed war. So before the Civil War battles were mainly memorialized through art and song, so poetry and painting and song, and it was often by survivors of the war and done after the fact, so it really served to glorify warfare, but photography forced citizens, especially those who were not participating in the war who believed it to be an honorable cause to come into terms with the true cost and the brutality of war. And no image perhaps so greatly captured this loss and this violence as the very famous photograph the dead of antietam by Alexander Gardner in 1862. And so this is the battlefield after the battle of antietam were 4000 men lost their lives and as you can see bodies are just scattered across the length of this fence. And people were deeply affected by this photograph and others that were taken during the war. Okay, so our first poet that we're going to look at is Walt Whitman. Very famous American poet born in 1819 to a family of fairly modest means, but a family with a deep sense of American patriotism. To get a sense of this patriotism, I note that Whitman's younger brothers were named Andrew Jackson Whitman, Thomas Jefferson Whitman and George Washington Whitman. So you can see that patriotism running through there. Weapon today is best known for his transcendentalist Magnus Magnum Opus leaves of grass, which he continued to edit and republish his entire working life. And ironically, the work only gained national attention after a Boston district attorney objected to it in one of the work's final publications. But Whitman was also a nurse during the Civil War. And in this time, he visited by his own rough estimate about 600 military hospitals and he saw somewhere between 80,000 to a 100,000 patients during his time in the war. And he then composed his collection drum taps in 1865, where he published it in 1865, which recounted his experiences. He's the father of free verse poetry, of course. So unmetered poetry and then he regularly employed anaphora and apostrophe. So in Afro being repetition of a word of phrase at the beginning of a line and then apostrophe is directing a particular line or even an entire poem to an entity that can not speak back. So a spiritual entity or a thing or an idea rather than a person. For an individual. All right, so here's our first poem to take a look at. We've got three Whitman poems and two Melville poems that we'll look at. So here is Whitman at the very beginning of the war. This is right when the war is breaking out. He writes his poem. It's called beep beep drums. Beat, beat, drums, blow bugles blow through the Windows through doors. Burst like a ruthless force into the solemn church and scatter the congregation. And to the school with a scholar of studying, leave not the bridegroom quiet. No happiness must he have now with his bride nor the peaceful farmer any piece plowing his field or gathering his grain. So fierce you were and pound you drums. So shrill, you bugles blow. Beat drums blow bugles blow over the traffic of cities over the rumble of wheels in the streets. Our beds prepared for sleepers at night in the houses, no sleepers must sleep in those beds, no bargainers, bargains today by day. No brokers are speculators. Would they continue? Would they be with the talkers be talking with the singer attempt to sing with the lawyer rise in the court to state his case before the judge? Then rattle quick or heavier drums, you bugles, wild or blow. Beat, beat drums, blow bugles blow. Make no parlay, stop for no expostulation. Mine, not the timid, by not the weeper or prayer, by not the old man, beseeching the young man, that not the child's voice be heard, nor the mothers and treaties make even the trestles to shake the dead where they lie awaiting the hearses. So strong you sound so terrible drums. So loud, you bugles below. So this is a classic example of anaphora. I'm sorry, I have apostrophe, although he does have an Afro as well. But he's not just talking about the bugles and the drums, but he's addressing the poem to the drums and the bugles. And he's, in fact, commanding these instruments to beat and to blow, there's an urgency, especially in that first line with each word receiving an exclamation point after it. He demands that these instruments burst like a force of armed men into the security piece and domesticity of American life. There are no boundaries. That are secure from this call to arms. There is no ritual sacred enough. So there is no, as you make your way through the poem, no praying, no studying, no wedding, no farming, no sleep, no commerce, no talk, no song, no law. There is only war, and then even in the third stanza, we come to the more timid, quote unquote, timid citizen. So he speaks of old men, children, mothers, those who would weep or pray, and he wants these voices to be drowned out by the sounds of war. So there's this very, very jingoistic kind of call to war here from Whitman. 1861, the beginning of the war, and we find a similar kind of poem. From Whitman. And a similar style, just as he addressed the previous poem to the bugles and two. To the drums, so too does he actually address this poem to the year itself in 1861. And as he makes his way through the poem, we'll see that he not just addresses the year, but he personifies it. So let's read this poem and then talk a bit about it. Or 1861. Armed year, year the struggle, no dainty rhymes or sentimental love versus for you terrible year. Not you as some pale poet, seated at a desk, lisping cadens piano. But as a strong man, erect clothed in blue clothes, advancing, carrying a rifle on your shoulder with well gristle body and sunburnt face and hands with a knife in the belt at your side. As I heard you shouting loud, you're sonorous voice ringing across the continent. Your masculine voice a year as rising amid the great cities amid the men of Manhattan. I saw you as one of the workmen. The dwellers in Manhattan, or with large steps crossing the prairies out of Illinois, Indiana rapidly crossing the west with springing gate and descending the alleghanies or down from the Great Lakes or in Pennsylvania or on deck along the Ohio River or southward along the Tennessee or Cumberland rivers or a Chattanooga on the mountaintop, saw I, your gate and saw I, your sinewy limbs. Clothed in blue bearing weapons robust year. Heard you determined voice launched forth again and again. Year that suddenly sang by the mouths and the round lipped cannon, I repeat you hurrying crashing sad and distracted year. So again, we see in Whitman employing free verse and apostrophe, this time the audience is the year itself, 1861. It's personified as one of the working men, the dwellers and Manhattan, but he offers a number of different possibilities or with large steps crossing the ferries out of Illinois and Indiana or down from the Great Lakes or in Pennsylvania or on deck along the Ohio River. So the personification of 1961 is not just singular, but it is all of those who are called into the fight. Particularly from the north. It's the embodiment of the democratic body. Like the personification of 1861, the poem itself does not want to fall into what he calls an initially the dainty rhymes or sentimental love versus. So here we see the first instance of a poet conscious of how he is memorializing the moment as he is doing so. So he wants to not just consider the year and the war, but also the way in which he is addressing that year. Which brings us to Herman Melville, our second poet and focus today. Melville is born sorry 1861 is incorrect. He's born in 1819. So he's born in 1819. And to a fairly well off family, his father was a successful importer and merchant. Sudden death, though, in 1832, left the family with significant debts and their finances dwindled significantly. And this is a side note. I'd like to make the point here that Whitman was not the only one with fabulous brotherly names. Melville's brother gens and fort took over the family business after his father died. 1830s Melville attended Albany classical school where he studied classical literature began writing poems. And then the 1839 Melville signed up to be a cabin boy in the saint Lawrence. Thus beginning a life and love of sailing. So Melville, in some ways, is to the American oceans as Twain is to the rivers, his knowledge of ocean sailing was really unparalleled. He first wrote about sailing in his book typee, a PEEP at Polynesian life in 1864, which told the mostly true story of Melville's experiences on the Lucy Anne and then later the USS United States. A story which is, in fact, pretty incredible includes moments of desertion, it includes two mutinies and Melville and a few other sailors were also, in fact, captured by an honest to goodness cannibal tribe. Fortunately, he obviously was able to get out of that alive. Ironically, the book that would later bring Melville, his greatest acclaim, although posthumously was Moby dick in 1851, but it was so poorly received in his lifetime that it eventually led him to stop writing prose altogether. And so from about 1860 to the end of his life in 1891, he wrote only poetry. His poetry is quite good. It's very lyrical, and then more traditional that went. And you can even see elements of modernism start to creep into his poetry. And he regularly employed meter rhyme illusion and metaphor, illusion, of course, just being a reference to outside works, mythology, biblical illusions, that sort of thing. Okay, so a couple of poems from him. So first of all, a utilitarian view of the modern flight. So the subject of this poem is the USS monitor, which was an ironclad union warship that defeated the confederate sides of Virginia, worship during the spring of 1862, and it was the first ever battle between two ironclad warships in history. The utilitarian aspect of this poem speaks to the detached tone that the poem will adopt. The terrifying machinery of war is presented in this poem without passion and that's a direct quote from the poem. So like 1861, this poem asks in the first stanza how a poet is supposed to write a poem about war. So drawing upon again the title, it's really asking what the utility of poetry is in times of war. Somewhat ironically, the poem begins with the first line. You see there is plain to be the phrase yet apt to be the verse, but the poem is really anything other than plain and simply apt. And so it's almost as if Melville is saying that poetry can not help, but obscure the content that it is, in fact, trying to deliver. So let's take a look at this at this poem and see how he discusses the monitor's fight here. Playing be the phrase, yet apt to be the verse, more ponderous than nimble. For since Grimm's war here laid aside his painted pop toward ill befit over much to ply the rhymes barbaric symbol. So there's great irony there that he wants to avoid rhyme that then the very line that he says rhymes symbol and nimble rhyme. Hail to the victory without the God of glory, zeal that needs no fans of banners, playing mechanic power applied cogently in war, now placed where war belongs among the trades and artisans. So war becomes work. Yet this was battle and intense beyond the strife of fleets heroic, deadlier, closer, calm, mid storm, no passion. All went on by crank pivot and screw and calculations of calorics. And it's not just work, but it's industry. Needless to dwell, the stories know, and the ringing of those plates on plates still ring a round the world, the clangor of the blacksmith's fray, the anvil den resounds this message from the fates, war shall yet be and to the end. But war paint shows the streaks of weather. War yet shall be, but the warriors are now but operatives. War is made less grand than peace and descend runs through lace and feather. So notice only not only what is present in the poem, but what's absent, which is soldiers lives. There's only one mention of the warriors and that's at the very end. The machinery of war really takes place in the actual live lost. Melville's other poem that I'd like to take a look at today is the college colonel. So as mentioned earlier, the war was largely fought by young boys. In this poem, a former college student now a kernel and a colonel, if the idea of sense of the rank would have been the senior field grade military officer. So just below a Brigadier general. So think about that that we have a college kid who is essentially become a field marshal. He's the same rank as a captain in the navy. And he returns home here at the end of the war. He's greeted as a hero, so we'll get a line in the I think penultimate stanza where it's hats off to the boys. So the citizens of this town are throwing their caps at him. But in reality, he feels that he has lost himself in the war. Sorry, just trying to. Oops. Okay. So the college colonel, he rides at their head, a crutch by his saddle, just slants and view. One slung arm and splints you see. Yet he guides his strong steed, how coldly to he brings his regiment home. Not as they filed two years before, but a remnant half tattered and battered and worn, like has to waste soldiers who stunned by the search loud roar. Their mates dragged back and seen no more again and again breast to surge and at last crawl spent to the shore. They still rigidity and pale in Indian aloofness lounge his brow. He has lived a thousand years, compressed and battles pains and prayers, marches, and watches slow. They're welcoming shouts and flags, old men, old men off hat to the boy. Reads from gay balconies fall at his feet. But to him, there comes alloy. It is not that a leg is lost. It is not that an arm is maimed. It is not that the fever has rats. Self he has long disclaimed. But all through the 7 days fight and deep in the world at his grim and in the field hospital tent. And Petersburg crater and dem lean brooding in Libya and there came a heaven. But truth to him. Okay. So in this poem, we see a college colonel returns and finds that while he is physically survived the war, although just barely, we have mentioned an amputation, so a leg that he has lost and a fever, so he was, you know, endure disease, but his self, self he has long disclaimed. So his self has long been sacrificed to the war. And it is perhaps the latter sacrifice that was necessary to preserve the former physical survival. But note to all of the illusions to the battles fought in the final stanza. So 7 days fight, the wilderness, Petersburg crater, and Libby, all were very, very gruesome battles that colonel would have fought in. And indeed, they would have been sewn onto the regimental color. So as he would have been returning home with his troops, the regimental colors would have had the names of these battles. So it into the flag. Melville then, in the end, offers a new truth, what truth came to him, and that truth punctures the romanticism of warfare. That this is not a great hero who is returning home again his home, the name of this place is not even meant. But is in fact a man who has lost his soul and wore, and then we're going to come to the final poem for today, which is a Whitman poem digital strange. I kept on the field one night. But before we do that, it's interesting, I think, to put this poem in context with the Protestant notion of the good death. So a vigil is a gathering of family and often a priest for when someone is gravely ill or mourning, prayers and voters are often made visuals extend from death to burial so that the body is never left alone. And the idea of a good vigil was incredibly important to antebellum Americans. In the modern world, of course, we have greatly outsourced death. It's not something that we really think about or want to talk about. But death occurs mostly outside of the home now. And it is, once the individual is dead, then the body is cared for, not by family members, but by professional undertakers and those who work in crematoriums. And even the funeral is largely arranged by those outside of the family. But an antebellum America, though, death was not only incredibly more common, but it was also more personal, those deaths took place in the home, and it was the family members who were then responsible for burying the body, usually within 24 hours. So the idea of the good death was widely discussed. And if you were a good Protestant, you thought about your death a lot. And especially as one got older and how you wanted to die. So there were, you know, manuscripts and speeches and books that were written on this topic. And there were great number of instructions. So a good death included the following. The individual should be surrounded by loved ones. The dying individual should be administered last rights by a priest and should have a final profession of faith, and then the dying shit uttered the last words. And these words were really thought about in advance. So they would have been prepared words. After the death, loved ones extended this good death by practicing appropriate morning rituals, which include black dresses for women, black armbands for men, and then even composing letters with black bordered stationary. So it was very highly ritual. But the Civil War, of course, disrupted this possibility of the good death. Half of all soldiers who died were buried anonymously without grave markers. And it's really tragic the ways in which these men and those around them tried to try to offer semblances of good death to these soldiers. So there are instances, for instance, of delirious soldiers and field hospitals who were then surrounded by nurses who pretended to be their sisters and even their mother. And the soldier not knowing the difference because they were, again, delirious. Believed them to be surrounded by loved ones, a soldiers would carry pictures of their family members in their uniform. And so there are times and even images of young men who are dead on the battlefield and they are surrounded themselves with the pictures of their families. So as to be surrounded by their family and death. And then army chaplains after battles were over army chaplains run out into the battlefield to try to administer last rights to as many dying soldiers as they could. So they would literally just go sort of down the line as it were in order to extend these final last rights and to then also record the last words of the dying man. So it's with that in mind that we can come into our final poem of the day, which is vigil strange I kept on the field one night. This is what women. Digital strange I kept on the field one night, when you my son and my comrade dropped at my side that day, when I but gave which your dear eyes returned with a look, I shall never forget. Untouched of your hand to mind, oh boy, reached up as you lay on the ground. Then onward I sped in the battle, the ever contested battle to late in the night relieved to the place that last, again, I made my way, found you in death so called dear comrade, found your body, son of responding kisses, never again on earth, sorry, beared your face in the sunlight. Starlight, curious the scene cold blue, the moderate night wind. Long there, and then in vigil, I stood dimly around me, the battlefield spreading visual wondrous and vigil sweep there in the fragrant silent night, but not a tear fell. Not even a long drawn side, long, long I gazed, then on the earth partially the kinase sat by your side, leaning my chin and my hands, passing sweet hours immortal and mystic hours with you, dearest comrade, not a tear. Not a word, digital silence, love and death, vigil for you, my son and my soldier as onward silently stars aloft eastward new ones upward stole vigil final for you, brave boy. I could not save you, swift was your death. I faithfully loved you and cared for you living. I think we shall surely meet again till at last lingering of the night, indeed, just as the dawn appeared, my comrade I wrapped in his blanket. Enveloped well his form folded the blanket well, tucking it carefully overhead and carefully under feet. And there and then and bathed by the raising sun, my son and his grave, and his rude Doug grave, I deposited. Ending my vigil strange with that vigil of night and battlefield dim vigil for boy of responding quizzes, kisses, never again on earth responding vigil for comrades, swiftly slain, vigil I never forget how his day brightened, I rose from the chill ground and folded my soldier well in his blanket and buried him where he felt. So just a really beautiful poem that I think rather speaks for itself. But we see Whitman there trying to give vigil in a sense to all the soldiers that would not have been able to receive one. The repetition of vigil, the anaphora of vigil in this poem. I think every time that word is mentioned, it is then offered to another soldier. He not just calls the soldier comrade. He calls him son, creating that familial bond, and the lines feel so carefully wrought almost to sort of merge with this idea of the blanket that he's wrapping around the young soldier, the lines also wrap themselves around the vigil that is being kept poetically anyway for all of these fallen. Soldiers. All right. So, sorry, bye. There we go. Okay. So that is, that's it. For the presentation. Go ahead and start.