Bartolomeo Cristofori Inventor of the Piano

College and University / Business

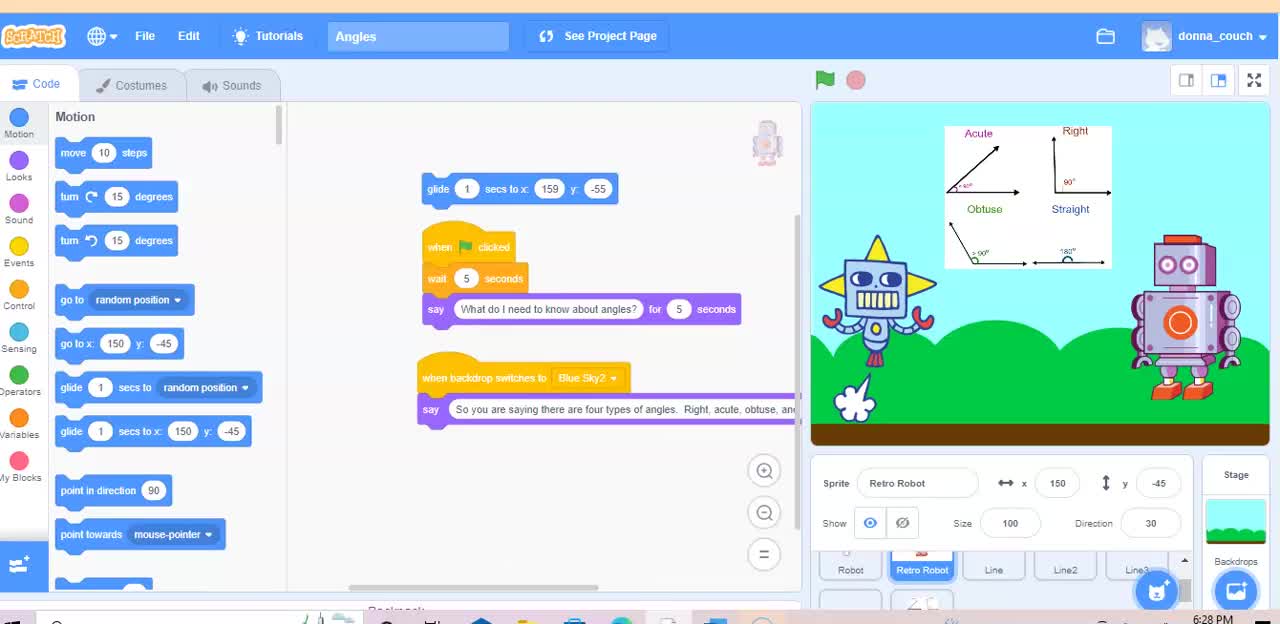

The Importance of the Piano The pianoforte, all the more generally called the piano, got to be, by the last quarter of the eighteenth century, a main instrument of Western workmanship music, for both experts and beginners. The cutting edge piano is an exceptionally flexible instrument fit for playing practically anything an ensemble can play. It can maintain contributes an expressive design, making every musical style and states of mind, with enough volume to be heard through any musical outfit. Comprehensively characterized as a stringed console instrument with a mallet activity (rather than the jack and plume activity of the harpsichord) fit for degrees of delicate and noisy, the piano turned into the focal instrument of music instructional method and novice study. Before the end of the nineteenth century, no white collar class family of any stature in Europe or North America was without one. Each significant Western arranger from Mozart ahead has played it, numerous as virtuosi, and the piano repertory—whether solo, chamber, or with symphony is at the heart of Western established proficient execution. Cristofori and the First Pianofortes The calm way of the piano's introduction to the world around 1700, in this way, comes as something of an amazement. The main genuine piano was concocted altogether by one man—Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, who had been delegated in 1688 to the Florentine court of Grand Prince Ferdinando de' Medici to look after its harpsichords and inevitably for its whole accumulation of musical instruments. A 1700 stock of Medici instruments specifies an "arpicimbalo," i.e., an instrument looking like a harpsichord, "recently designed by Bartolomeo Cristofori" with sledges and dampers, two consoles, and a scope of four octaves, C–c'''. The artist and writer Scipione Maffei, in his excited 1711 depiction, named Cristofori's instrument a "gravicembalo col piano, e strong point" ("harpsichord with delicate and noisy"), the first occasion when it was called by its possible name, pianoforte. A contemporary engraving by a Florentine court artist, Federigo Meccoli, takes note of that the "arpi cimbalo del piano e' strong point" was first made by Cristofori in 1700, issuing us an exact birthdate for the piano. Cristofori was a guileful designer, making such a complex activity for his pianos that, at the instrument's initiation, he tackled a large portion of the specialized issues that kept on confounding other piano planners for the following seventy-five years of its development. His activity was very perplexing and consequently costly, creating a hefty portion of its highlights to be dropped by resulting eighteenth-century creators, and afterward continuously reevaluated and reincorporated in later decades. Cristofori's keen advancements incorporated an "escapement" component that empowered the mallet to fall far from the string immediately in the wake of striking it, so as not to hose the string, and permitting the string to be struck harder than on a clavichord; a "check" that kept the quick moving sledge from skipping back to re-hit the string; a hosing instrument on a jack to quiet the string when not being used; secluding the soundboard from the strain bearing parts of the case, so that it could vibrate all the more uninhibitedly; and utilizing thicker strings at higher strains than on a harpsichord. Cristofori's Surviving Pianos Three pianos by Cristofori make due, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (1720, 89.4.1219); at the Museo Strumenti Musicali in Rome (1722); and at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum of Leipzig University (1726). The Metropolitan's Cristofori, the most seasoned surviving piano, is in a plain wing-formed case, apparently looking like a harpsichord. It has a solitary console and no exceptional stops, in much the same style as Italian harpsichords of the day. (The consoles of the two other surviving pianos by Cristofori can be moved somewhat so that stand out of the two strings of every pitch will be struck, i.e., una corda, along these lines calming the whole instrument.) The sound of the Museum's 1720 Cristofori contrasts impressively from the advanced fabulous piano. Its reach is narrower—54 instead of 88 keys—and its more slender strings and harder mallets issue it a timbre closer to a harpsichord than a current Steinway. Maffei remarked that, due to its to a degree quieted tone, Cristofori's piano was ideally equipped for performances or to go with a voice or single instrument, instead of for bigger group work. To be sure, a contemporary harpsichord was a louder and more splendid instrument, however did not have the capacity to react to the quality of the player's touch, thus could attain to no huge degrees in element interpretation. Like the piano, the clavichord (1986.239) is additionally fit for nitty gritty degrees of uproarious and delicate controlled by the player's touch, yet this cozy stringed instrument is general so delicate that it can scarcely be heard a couple feet away, as is futile in gatherings or in show. Cristofori's development was at first ease back to catch on in Italy, however five pianos by Cristofori or his understudy Giovanni Ferrini were obtained by Queen Maria Barbara de Braganza of Spain, supporter and understudy of Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757). Several Scarlatti's more than 500 single-development console sonatas may have been planned for piano, instead of harpsichord as has long been expected. The soonest music most likely composed and distributed particularly for the piano were twelve Sonate da cimbalo di piano e strength detto volgarmente di martelletti (Florence, 1732) by Lodovico Giustini (1685–1743), committed to Don Antonio of Portugal, uncle of Maria Barbara and another understudy of Scarlatti. The sonatas contain nuanced articulations, for example, più strength and più piano, fine element degrees difficult to execute on a harpsichord. Maffei's portrayal, which incorporates an outline of Cristofori's activity, was interpreted into German and included in Johann Mattheson's Critica musica of 1725, where it was likely perused by Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753), the critical Saxon court organ manufacturer. In light of Cristofori's configuration, Silbermann started deal with his own pianos in the 1730s. An early model was released by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) as having too overwhelming a touch and excessively powerless a treble. With genuine direct experience of one of Cristofori's instruments and consequent enhancements, Silbermann's pianos were more effective, prompting the buy of a few by Frederick the Great, ruler of Prussia (r. 1740–86). Bach later adulated Silbermann's pianos, set so far as to turn into a business specialists for his instruments, consequently expanding the impact of Cristofori's creation in focal Europe amid the years taking after the Paduan instrument.